Native black poplars Populus nigra betulifolia at Hillside House

Summary

- Sixteen male native black poplars Populus nigra betulifolia (clone 25) have been planted in a strip approximately 60 metres by 12.

- Two female native black poplars (clone 32) are also planted in the same strip.

- Trees are planted in mounds to prevent waterlogging of the roots.

- Annual growth has been around 1.0 metres per year.

- Nearest-neighbour gaps are set at 8 metres.

- Native black poplars on the meadow at Hillside House

- Planting stages: the A-group trees

- Planting stages: the B-group trees

- Planting mounds

- Final layout of poplars on east side of meadow, 2017

- DNA fingerprinting tests, summer 2016

- Progress

- Growth rates of native black poplars 2016, 2017 & 2018

- Some background: why plant native black poplar?

- Native black poplar Populus nigra betulifolia

- Decline of native black poplar

- Hybrids and cultivars

- Invertebrates associated with poplars

Native black poplars on the meadow at Hillside House

One of the main projects here at Hillside House is to develop a small strip plantation of native black poplar Populus nigra betulifolia.

Low-lying parts of the eastern counties of England probably once had extensive woods or forests partly composed of this now rare native subspecies.

Following the suggestion of Oliver Rackham in some of his classic publications, the plan has been to grow perhaps 20 or more native black poplars here on the meadow.

The meadow is just north of the pond and looks almost ideal for native black poplar.

The soil is quite peaty near the surface. Further down is a more gravelly layer containing a lot of finely divided flint.

The ground in this part of the plot is damp for much of the year. In the winter months the water table is often only 10 to 20 cm below the soil surface. However, since 2013, flooding on this meadow has never been more than local and short-term.

Planting stages: the A-group trees

The original planting was of 50 trees in autumn 2014.

These first trees were placed in a strip on the west side of the meadow.

Trees were obtained as bareroot whips from British Hardwood Tree Nursery.

The picture shows the typical features of the original batch of plants (the A-group). The leaves are rather stiff, flat, and 'solid'-looking, with small rounded teeth (not obviously hooked). The laminas tend to be rather dark green. The petioles are hairy, though not excessively so (a handlens is required to see the hairs).

These A-group plants have gradually developed Pemphigus galls, though none were present at first.

After the initial planting, survival of these trees was poor and only 16 or 17 (31%) were still alive by the end of summer 2015.

The most likely explanation for the poor survival is that that some of the whips were originally put into ground that was too soggy.

However, an encouraging result was that DNA testing showed that the A-group trees were genuine P.n.betulifolia clone 25 (a male clone).

Planting stages: the B-group trees

After the poor return on the A-group trees, more whips were sourced and planted in winter 2015/16. The intention at this stage was to end up with around 40+ good trees. The new material came from a nursery in Norfolk.

Spacing between nearest neighbours was set at around 3.5 to 4 metres. Later, after visiting sites where mature native black poplars were present, it became obvious that these gaps were too tight.

Planting mounds

In order to improve survival rates, the new B-group trees were planted in shallow mounds of soil, to prevent the young roots from becoming waterlogged. The mounds were approx. 30 cm high and were covered over with turves to stop them eroding away and collapsing. This work entailed moving substantial amounts of sand and soil to the planting area (at least 200 kg per tree!). The new trees also went into the best patches of the field, where the roots would initially be clear of the top of the water-table. Once established they were expected to be able to tolerate occasional wetter conditions after heavy rain.

Unfortunately, DNA tests on trees from the B-group show them to be irrelevant for the conservation of native black poplar. Some at least had as one parent 'Vereecken', a fast-growing form of P.nigra but not betulifolia.

Despite this frustrating outcome, there was a useful result from the work on the B-group trees. Survival of trees planted in mounds was much better and growth rates were (statistically) significantly higher. Thus the measures taken (mounds, stakes, wire-netting etc) have clearly been effective.

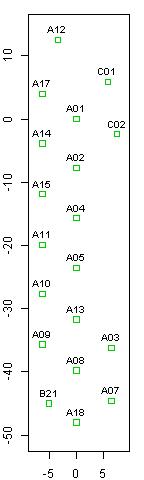

Final layout of poplars on east side of meadow, 2017

After a lot of careful thought, a somewhat drastic decision was taken in early 2017 to move all the surviving poplars to the eastern side of the meadow.

After a lot of careful thought, a somewhat drastic decision was taken in early 2017 to move all the surviving poplars to the eastern side of the meadow.

Decades ago, a few hybrid poplars were planted along the south-eastern boundary of the meadow. It had become clear that areas of reedfen downwind of these hybrid trees tended to get clogged with poplar leaves in the autumn.

Because the original 2014 poplar planting area was on the western edge of the plot, leaf-fall from mature trees there would eventually tend to be carried by the prevailing wind into the bulk of the reedbed. With the original layout, leaf-fall would have badly degraded the reedbed habitat.

The 2017 transplanting work was left rather too late in the 'bare-root' season for comfort, but was complete by March 30th 2017. By late April all the trees were showing good leaf development and appeared to be in good health.

In the layout plan shown, distances are in metres and the positive y-axis corresponds roughly to due north.

Nearest-neighbour gaps were set at 8 metres.

DNA fingerprinting tests, summer 2016

As leaves developed on the B-group trees, it became clear that they were variable and some looked quite different from the A-group trees.

Samples of four trees were sent off to Forest Research at Roslin for DNA fingerprinting.

Many thanks go to Stuart A'Hara for doing the DNA work.

DNA results are as follows:

- The A-group trees (planted in 2014) match Populus nigra betulifolia clone 25 in Roslin's database. This is a male clone.

- Clone 25 is represented by a tree at Burwell, near Cambridge.

- The B-group trees were a confusing mixture. At least some of them had hybrid-like features (leaves were hairless, floppy, almost translucent, with wavy edges, and with large hooked teeth on the leaf edge).

- Two B-group trees (B20 and B21) appeared to be derived from a fertilization between 'Vereecken' as one parent, and an unknown P.nigra clone as the other parent. 'Vereecken' is a vigorous form of P.nigra. So in other words, they were Populus nigra but not 'native' black poplar. There was no evidence that either B20 or B21 had any genetic contribution from P. deltoides. Tree B21 is shown as a young whip.

- Another of the DNA-tested B-group trees (B47) appeared to be derived from fastigiate P.nigra. According to Ken Adams, this is an unhybridised, one-locus mutant of P.nigra. (This tree was scrapped).

TreeEbb has some pictures of leaves of 'Vereecken' (webpage is in Dutch). The leaf shape is similar to that of B20 and B21 (petioles are quite long, laminas are like a stretched diamond with rather widely-spaced teeth, especially along the hind edge).

After the DNA results were available, all B-group trees were scrapped, with the exception of B21, which has been saved and moved.

Progress

In 2016/17 all B-group trees were lifted and scrapped, as planned (with one exception -- tree B21).

- All A-group trees, except A18, were moved to the east side of the meadow in a strip close to the boundary ditch. All are now in shallow raised mounds surrounded by wire-netting. They are also protected using vole- and rabbit-guards. Old carpet is placed round the tree base to suppress weed growth. This has become the standard planting system here for native black poplar.

- In February 2017 two clone 32 female whips were obtained from Nowton Park in Suffolk. These are derived from cuttings taken from a veteran tree in the Abbey Gardens in the centre of Bury St Edmunds (pictured).

- The female trees C01 and C02 are progressing well and have grown at rates similar to those of the males.

Growth rates of native black poplars 2016, 2017 & 2018

| statistic | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean increment (in metres) | 1.172 | 1.129 | 0.994 |

| sample size n | 5* | 18 | 18 |

| standard deviation | 0.127 | 0.229 | 0.234 |

| minimum | 0.99 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| maximum | 1.29 | 1.62 | 1.39 |

* Note -- only five A-group trees were grown in mounds in 2016.

(Year differences in annual growth are not statistically significant, but 2018 was a dry summer.)

Detailed analysis of native black poplar growth at Hillside House using R (pdf file, A4 pagesize)

[Note -- if using Firefox you may need to alter settings as follows to correctly display italics in the pdf document. Go to Tools > Options > Advanced > uncheck 'Use hardware acceleration when available']

Some background: why plant native black poplar?

Black poplar Populus nigra is a species with an extensive global range.

The species is found over much of central and southern Europe, across to central Asia and south to North Africa. Given the extensive range of this species, some might ask: why bother planting 'native' black poplars?

Native black poplar Populus nigra betulifolia

Populus nigra betulifolia is a very fine form of the species restricted to north-west Europe, including France, Netherlands and the southern half of England. It also occurs sporadically in Wales and has been planted extensively in the Manchester area. The core of the remaining population now seems to be in the Vale of Aylesbury.

P. n. betulifolia is characterised by the overall form of the tree (big, often leaning main stems with branches that tend to arch downwards initially), deeply fissured bark in old trees, 'bosses' on the main stems, details of the leaf shape, and hairy leaf petioles.

It seems likely that this form is indeed native to England and Wales. Perhaps it got here across the ancient land-bridge that once joined Britain to continental Europe.

Decline of native black poplar

Oliver Rackham says black poplar is recorded in medieval texts and manuscripts, and that even today some actual poplar remnants survive in the fabric of ancient buildings. The tree involved in these instances must be the 'native' type. According to Rackham, black poplar started to decline in the British countryside from around 1800 or earlier [2].

By the end of the twentieth century, the native form had become one of the rarest of the trees indigenous to the UK and Ireland. The population is down to a few thousand trees. Of these, only a few hundred are females, poplars being a group where individual trees are either male or female (i.e they are 'dioecious').

Rackham recommended that anyone with a suitable patch of land should consider planting the native type. His suggestion inspired the planting scheme at Hillside House.

His enthusiasm for black poplar may have been partly a response to the disastrous decline of elms in the 1970s. Elms are, like poplars, much associated with the lowlands and river valley flood plains. Elm disease wiped out the immense mature 'English' elms that formerly dominated the landscape in many areas and thus changed the countryside for the worse. Apart from being a superb landscape feature, the elms, often occurring in lines or hedgerows, provided valuable nesting sites for various species such as rooks.

Poplars may be less susceptible to disease than cultivated elms and could perhaps offer a way of partially compensating for the loss of elms.

Hybrids and cultivars

The problems with the B-group trees show that great care is required to distinguish native black poplar from the hybrids and cultivars that may be encountered.

Accurate identification of poplars is tricky, even for specialists. The only safe way is DNA fingerprinting (see Ken Adams' water poplar webpage).

The vast majority of the poplars planted in many places in Norfolk, for example in the upper Wensum valley, are sure to be hybrids or cultivars.

Invertebrates associated with poplars

Among the invertebrates found so far on these native black poplars are poplar hawkmoth caterpillars (Laothoe populi). The first caterpillar was found on tree A17 in September 2015, and almost completely defoliated its host plant, though the tree has since recovered well. Caterpillars were found on several more of the trees in 2016.

Interestingly, none of the B-group trees (of uncertain provenance) was found to be attacked by hawkmoth caterpillars.

The Pemphigus aphids have been mentioned. A psyllid has also appeared on the trees in 2018, causing reddish leaf-curl. (Psyllids and aphids are true bugs, order Hemiptera). Chinery says these insects are like miniature cicadas.

References

[1] The status and clonal distribution of Water Poplars, Populus nigra betulifolia in Essex and the features distinguishing them morphologically from the numerous exotic poplars now grown in the county.

[2] Rackham, O. 1986. THE HISTORY OF THE COUNTRYSIDE. J.M.Dent, London.